Donald Trump’s first speech to Congress as President of a new administration captures a moment of intense partisan division: “I look at the Democrats in front of me, and I realize there is absolutely nothing I can say to make them happy or to make them stand or smile or applaud, nothing I can do.”

The good news on this is that this partisan rancour is less pronounced among the general public than is widely estimated. Recent evidence finds that a type of question widely used in opinion polls exaggerates the gap in beliefs between people who support the Republicans and those who support the Democrats.

The research, published in the International Journal of Forecasting, is a collaboration between Jack Soll, a professor of management at Duke who is an expert on the Wisdom-of-the-Crowd, and Dave Comerford, a professor who directs Stirling’s MSc Behavioural Science.

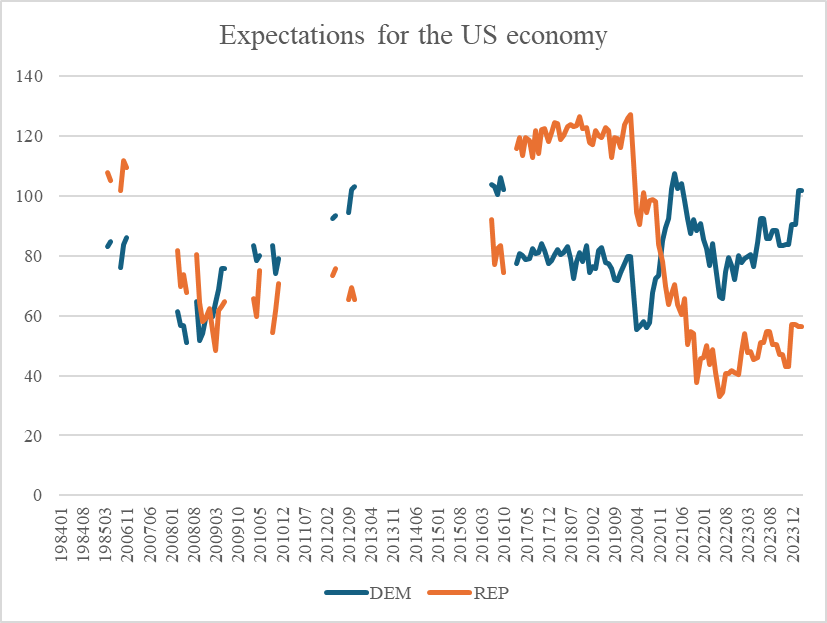

Figure I. The University of Michigan Index of Consumer Expectations, by Party Affiliation (data source: University of Michigan, 2024).

“The questions asked in leading polls evoke gut reactions, which are partisan-tainted” Dave explains. “For instance, the question Will the economy get better or worse over the coming year? is widely used in consumer sentiment surveys and by private polling companies. It consistently shows partisan responses – when the Democrats are in office Democrat voters are more optimistic than Republicans; when Republicans are in office, it is Republicans who are most optimistic.”

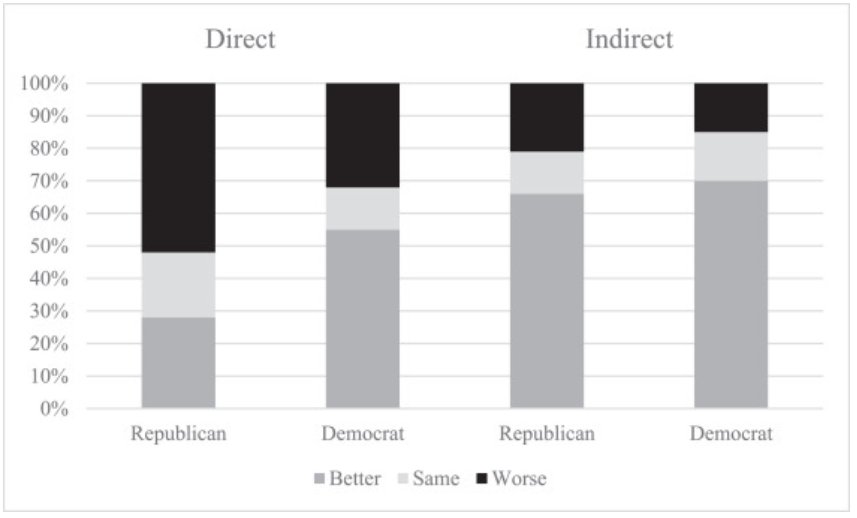

But when we asked the logically-equivalent two-part question “rate the economy today” and “rate the economy you expect a year from now”, Republicans implied trends that closely resembled those given by Democrats.

Figure II. Economic Forecasts Made by Partisans from Comerford and Soll (2024)

“The explanation is that the two-part question requires people to stop and think about what they are actually being asked, whereas the standard question let’s you answer with whatever first jumps to mind. So”, Comerford continues “when we asked people to estimate the change in approval ratings for Trump and for Biden we see Democrats reporting Biden’s polling data improved by 18 percentage points over just 3 months. But when we asked people to estimate Biden’s polling data from 3 months ago and also to estimate his polling data today, they were far more realistic in their appraisals.

There are two reasons why this result matters for the real world. First, the perception that polarisation is increasing is itself a source of polarization – it incentivizes voters to adopt more extreme and intransigent stances. Second, opinion polls equip partisans with data to distinguish “us” from “them” and so polling data informs the construction of political identities and policy priorities. By giving us a more realistic measure of what people believe Comerford and Soll’s work goes a little way towards finding agreement at a moment where that seems especially important.